“Stigma is a process by which the reaction of others spoils normal identity.”

(Erving Goffman)

At Provide, our central driving value is the belief in the fundamental and inherent worth of all people—including those who cause us discomfort. Often, this discomfort is a product of stigma: the negative view we hold of people because of a certain quality or circumstance. As providers of abortion referrals trainings, working with partners in fields that include domestic violence, HIV, and substance use disorder, stigma sits at the forefront of our work as well as that of many of our partner sites. Only by recognizing and working against stigma can we create systems that can truly provide patient-centered care for our clients. To that aim, we’re introducing a blog series on stigma that discusses how it shows up in health care and social service delivery; how to identify signs and symptoms of stigma at the individual, environmental, and structural levels; and how to contribute to a stigma-free workplace.

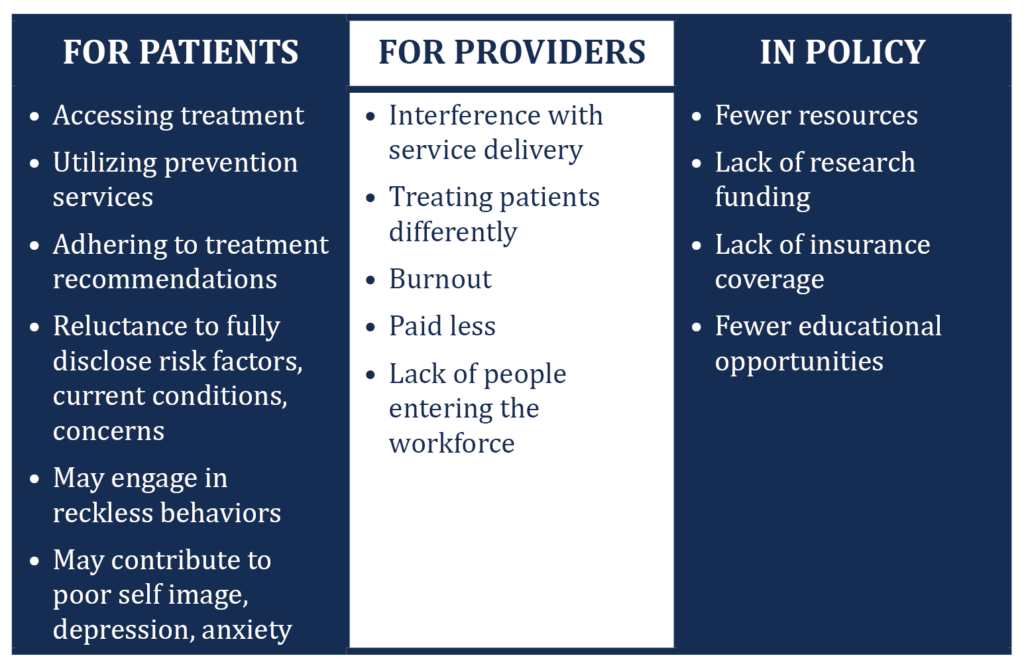

How does stigma show up in health care and social service delivery?

Stigma is an attribute of a person or group of people that is viewed negatively and may lead to avoidance, bias, stereotyping, and discrimination. Some examples of stigma in health care include not wanting to touch a patient living with HIV, refusing treatment to someone perceived as a drug user, and judging a pregnant woman who discloses having several children already or who doesn’t want to be pregnant. Healthcare providers can also experience stigma, for example, when a community doesn’t allow a provider to open an office because they don’t agree with the services that are being offered or are worried that the provider will bring “the wrong kind” of people into the community.

Our South Carolina State Coordinator, Shannon Ivey, describes the dual stigmas around sex and drug use that she has observed when conducting trainings. “The stigma of talking about sex and sexual health is at the core of the discomfort in talking about unintended pregnancy,” she states. “Many folks in the rural conservative South, even clinicians, feel discomfort around it.” During a recent training activity at a medically assisted treatment center in upstate South Carolina, Shannon and the trainees discussed all the reasons why a woman has sex. “When having sex for money or drugs came up as a reason, we got to have a ‘real talk’ conversation around what their clients may have had to do to survive abusive situations, such as having sex for money, for shelter, etc. I think [the trainees] fight hard not to characterize their clients with the stereotypes of opioid users we see in the media. When doing intake, they don’t always dig in to sexual practices, so these discussions can bring up things that they might have been avoiding talking about with clients. I love when this breakthrough happens in our training, and they get to try on new language about [unintended pregnancy].”

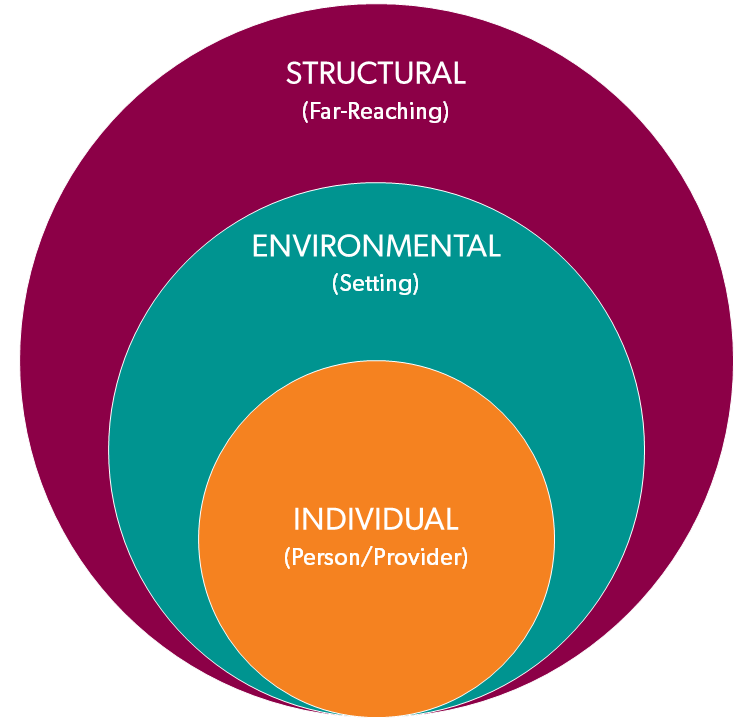

In seeking to identify where stigma might be present in your health setting, it can be helpful to think about stigma as occurring at three levels:

- Individual: from the individual provider who is interacting with the patient/client

- Environmental: from the immediate environment where health care and social services are delivered (the community in which you practice is also part of the environment)

- Structural: from the immediate policies and procedures that guide how health care and social services are delivered (this can include individual organizations, as well as local, state, and federal laws and policies)

These levels are interconnected. An individual’s stigmatizing thoughts and behaviors can influence the environmental and structural levels. As individuals, it is at this level that providers have the greatest ability to identify stigma and implement change.

Next: How to Identify Signs and Symptoms of Individual Stigma