“The provision of equitable and non-judgmental care is impeded by governmental and institutional policies and structures, such as financing of health care.”

At Provide, our central driving value is the belief in the fundamental and inherent worth of all people—including those who cause us discomfort. Often, this discomfort is a product of stigma: the negative view we hold of people because of a certain quality or circumstance. Stigma sits at the forefront of our work in providing abortion referrals trainings, as well as in the work of many of our partner sites, which includes domestic and sexual violence, family planning, HIV, primary care, and substance use disorder. Only by recognizing and working against stigma can we create systems that can truly provide patient-centered care for our clients. Our blog series on stigma discusses how it shows up in health care and social service delivery; how to identify signs and symptoms of stigma at the individual, environmental, and structural levels; and how individuals can help to remove stigma from their workplace.

How to Identify Signs and Symptoms of Structural Stigma

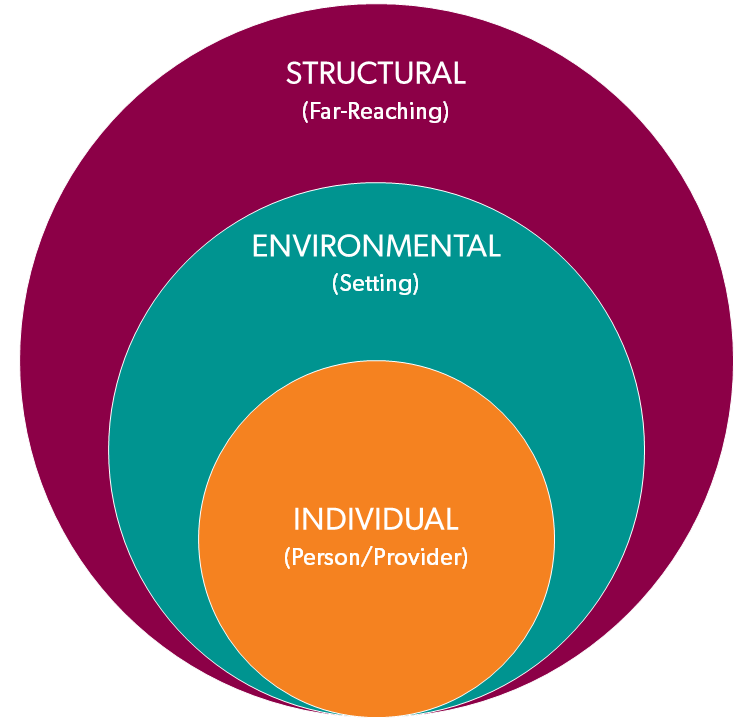

In seeking to identify where stigma might be present in your professional setting, it can be helpful to think about stigma as occurring at three levels:

Individual: from the individual provider who is interacting with the patient/client

Environmental: from the immediate environment where health care and social services are delivered (the community or clinic in which you practice is also part of the environment)

Structural: from the immediate policies and procedures that guide how health care and social services are delivered (this can include individual organizations, as well as local, state, and federal laws and policies)

These levels are interconnected. Individuals can influence their environment to be stigma-free, but Environmental change requires leadership buy-in. The Structural level can be most effective to reducing stigma among a large population, but changes at this level can face significant opposition and take a substantial amount of time for people to agree on changes and then implement them.

These changes can make an enormous difference in how clients experience their care, as they did for a client we recently interviewed. She related:

“The last time, you know, I felt real judged….The lady in there acted like I was just a lousy parent because I hadn’t been taking no prenatals or anything….They’re not as judgmental now, and I feel like they’re there to listen to me and understand my circumstances and where I’m coming from instead of just judge….It was better this time. I kind of felt like I was at home, talking to my husband or my mother. They really, they did a great job when they got the improvement that they got.”

While some forms of structural stigma may seem out of our control, there are steps we can take to ensure that stigma in our own workplaces is mitigated so that we can provide the best care possible.

First, ask questions to help you determine how structural stigma exists in your workplace, such as:

- Does staff have access to information on how to take action if a person has been discriminated against?

- Are people with particular health conditions or experiences (such as drug use, abortion, mental health, etc.) involved in quality improvement and anti-stigma activities?

- Do forms, policies, or other types of communications include stigmatizing language?

Example: A treatment provider was required to provide HIV education at intake. This education consisted of a page of bullet points that included statements such as: “If I become HIV positive I cannot be denied housing.” This documentation is stigmatizing because it assumes that people are HIV negative or that they know their HIV status. Although this paperwork was implemented on the structural level, an individual was able to create a new document that provided education and was not stigmatizing to patients living with HIV and those who don’t know their HIV status. This new document was eventually approved by the organization and was implemented across their system.

Next, explore the following steps for implementing policies that combat structural stigma:

- Identify a need(s) for policy.

For example, reduce confusion among employees regarding how to handle positive HIV tests. - Determine policy content.

Why does our organization need this? What are the desired outcomes? Who is responsible for carrying this out? - Obtain support from managers and supervisors.

Be prepared to address some of the questions you asked in the previous steps, including why the organization needs the policy and exactly how it is in alignment with your organization’s goals. Don’t forget to listen for context as to why the current policy (or lack thereof) exists and what the manager’s major considerations are. - Communicate with employees about the policy.

Provide context, determine the best way to distribute the policy, provide an opportunity for staff to ask questions, and review the policy with new employees during orientation. - Update and revise the policy (recommended annually).

Be clear about who is responsible for updating and revising the policy and who should communicate to staff about any revisions.

It’s important to understand – and sometimes to reconsider – our own attitudes, even as we strive to provide professional care. Being vigilant about respecting client and patient autonomy includes heightening our awareness about ways that we enact stigma, usually unintentionally or even unconsciously. The following are some additional actions you can take to address stigma in your workplace:

- Individual Level

- Train staff on how to use a comprehensive and up-to-date list of referral resources that value patient autonomy, dignity, and worth.

- Train staff on how to recognize their biases and provide support on managing the tension that can arise when personal values conflict with professional roles.

- Provide staff with examples for how to document patient interactions without using stigmatizing language.

- Environmental Level

- Review patient-facing materials such as pamphlets or flyers for stigmatizing language and revise as needed.

- Include visuals (posters, infographics, etc.) in your lobby and exam rooms that are inclusive of patients from a multitude of backgrounds and experiences.

- Communicate on your website that your services are patient-led and provide referrals to resources that honor patients’ autonomy.

Previous: How to Identify Signs and Symptoms of Environmental Stigma